Tonmeister Breaks Tradition, ARIA Engineer Of The Year

ABC Classics in-house tonmeister of all trades, Virginia Read, is this year’s ARIA Engineer of the Year. It’s high time we got to know the first female in ARIA history to take out the award.

Story: Michael Smith

Photos: Daniel Sievert

On a sunny mid-October Tuesday morning at the Art Gallery of NSW, the winner of the 2013 ARIA Engineer of the Year was announced and an obviously completely nonplussed Virginia Read made her way up to the podium to accept her award.

Not because she was unworthy, by any stretch. Virginia has seen 21 of her productions nominated over the past decade; seven of those nominations even going on to win Classical Album of the Year. But individual recognition? Bupkis.

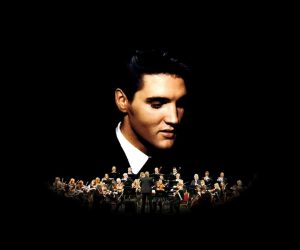

Virginia was getting used to being overlooked for the gong, and to suggest this win was any less unexpected is an understatement. As per usual, she was up against far more high profile nominees drawn from the commercial pop, rock and electronica worlds — Dann Hume for his work on the Alpine album, Seeing Red, Peter Mase for his on Empire Of The Sun’s Ice On The Dune, Nicky Bomba and Robyn Mao for their work on the eponymous album by the Melbourne Ska Orchestra, and Kevin Parker for engineering his band Tame Impala’s album, Lonerism [featured in Issue 91]. What hope could she hold for her work on an album of solo contemporary classical piano pieces, All Imperfect Things: Solo Piano Music of Michael Nyman, by Sydney-based pianist and composer Sally Whitwell? Even though Whitwell had previously taken out the 2011 ARIA Award for Best Classical Album, Mad Rush (Solo Piano Music of Philip Glass), it was yet another one of those times Read was overlooked — despite engineering, producing, editing and mastering the award-winning album.

But finally, this year, one of Australia’s foremost classical music producers and engineers got the recognition she deserved. Further adding to the landmark occasion is that Read has become the first female Engineer Of The Year in the ARIA Awards’ 27-year history. Read didn’t have it all her way though, missing out on Producer of the Year, for which she was also nominated. It went to Harley Streten, who you might know better by his stage name, Flume.

BEHIND THE TONMEISTER

In a career that has spanned more than 30 years, Read has engineered, produced, edited and/or mastered albums by everyone from the Mormon Tabernacle Choir to Teddy Tahu Rhodes, the Elektra String Quartet to the Australian Brandenburg Orchestra. Read’s most recent projects include engineering, editing, producing and mastering Andrew Ford’s album, Learning To Howl, editing and mastering Antony Gray’s Bach Piano Transcriptions, and recording, mixing and mastering saxophonist Amy Dickson’s album, Catch Me If You Can. Working in the field of classical music recording, Read has the advantage of a solid background not only in sound recording but also in music theory and practice.

“I did a music degree when I finished school,” she explains. “I actually studied composition and piano, but I was a very bad performer — I just suffered too badly from performance anxiety! And I wasn’t good enough to be a real professional musician. Through my composition studies I had got quite into electronic music, and from there much more into the recording of sound. This was in the ’80s and I must admit I was quite frustrated with the technology back then. Nonetheless, I found I enjoyed the technical side of it and was really interested in pursuing it more. But you couldn’t really study just classical music recording in Australia, so I found a place in Montreal where I went to study.”

It was at the Schulich School of Music at McGill University in Montreal, which offers the only program in North America for both a Master’s and PhD degree that, “follows the European Tonmeister tradition of training musicians to become sound engineers,” according to Read. The program was originally developed in 1979 in Germany by Professor Wieslaw Woszczyk for professional musicians like Read who wanted to develop the skills required in the recording and media industries.

“The Tonmeister degree is about really learning the technique of recording music,” said Read. “But always with more of the sense of a producer’s side to it as well, so that you’re recording music but with a real knowledge of the music. You had to have a music degree to get into the course. So I went off and did their prerequisite year because they only took about four or five people a year.”

CLASSIC SOUNDS

On gaining her degree, Read went to work at Classic Sounds in New York City from 1996 to 1999, which was set up by engineers Tom Lazarus and Tim Martyn. A multi-Grammy Award-winning recording engineer, Lazarus has recorded, mixed and mastered recordings for artists and ensembles as diverse as Ray Charles and Björk, Yo-Yo Ma and Ornette Coleman, the Vienna Philharmonic and Ravi Shankar. Martyn is also a two-time Grammy Award recipient for his recordings with Sharon Isbin and Evgeny Kissin. Not bad company to begin with.

“The studio employed three engineers,” Read remembers. “And I was working mostly in the post-production/editing side of things, as well as some recording. Sometimes I was on my own but a lot of the time I was the assistant engineer and tape op for Tom, back in the days when everything went to Tascam DA-88 [digital eight-track tape recorders],” she chuckles. “24-bit recordings were the top of the line. They were using 16-bit DA-88s fed by Prism Sound converters. They had a unit that allowed you to bit split and record four channels of audio at 24-bit using the eight tracks on those Sony Hi-8 tapes. Then we’d bring it all back to the studio and load it onto their Sonic Solutions DAW, using what today are laughably small hard drives.

“And that was also in the day when classical music was almost always mixed live. Very rarely would you have the luxury or the facilities to multi-track, especially as a lot of classical music happens at concert halls or churches. So it was all location recordings — there are a few venues in New York City where we’d record, but once I even drove the entire kit all the way to Toronto for a recording, on my own!

“Recording digitally is so much more creative and it does allow you to get even more out of a recording session, knowing what you can do with editing. When multi-tracking became a more realistic thing, it meant you could focus even more on producing at a recording session, rather than always having to be thinking of the balance and following the score.

“For classical music, I really love the dynamic range, the frequency range, that cleanness of digital recording; the mixes I’m doing now just have a lot of impact. When someone listens to my CDs, I want them to feel really involved with the musician, as though they’re right there with them, immediately engaged with what they’re hearing. I still love the sound of acoustics; I love the sense of having instruments in a space you can hear, but in a way that sounds as if you’re there with them.”

MERGING TO PYRAMIX

Today, as ABC Classical’s in-house engineer/producer, Read uses a Merging Technologies Pyramix system, which combined with the MassCore Engine and Horus interface, is currently one of the most powerful, best sounding and flexible audio production systems on the market. A single Pyramix MassCore system is capable of recording up to 384 discrete audio channels simultaneously. As it happens, Read’s experience with Classic Sound’s Sonic Solutions system has proven invaluable.

“The ABC did have a Sonic Solutions system, but I remember, even in 1999, Sonic was starting to be a bit frustrating for users, and each time they released a new version, it would be worse,” Read recalls with a laugh. “It was funny, all these big studios just weren’t upgrading because no one dared to. The system in the ABC was limping along, but it came to a point where I needed to upgrade. It was when Pyramix really started to take off and it was clear that all the people who had liked and used Sonic were all shifting to Pyramix. So I ended up making that choice as well.

“Now with drives being as huge as they are and the fact the speed is so reliable, you can multi-track record into the system. And Pyramix sounds really good, its data-handling is superb, and its editing capabilities come from the philosophy of what Sonic did, but dramatically improved.” And unlike the Sonic system, Read isn’t at all worried about upgrading the Pyramix, having just taken her facility from trusty version 6.0 to 8.1.

Read’s move from just being a recording engineer to also taking up the producer’s reins was prompted by her experience at Classic Sound. Homesick, she returned to Australia in 2000, and kept finding herself “a bit frustrated with the producers!” she said. “I had worked with some really wonderful producers in The States, so I knew what you could get out of a musician and a recording session. Rather than just documenting the performance, I was much more interested in making really wonderful recordings. So through necessity and frustration, I decided I had to produce as well as engineer.

“There was a period where I was either an engineer or a producer and I would often get frustrated as a producer, ‘I wish the engineer would do this…’ And as an engineer, ‘Ah, the producer just missed that!’ or ‘No, you should make them do it again.’ You can really thank the technology that you can engineer and produce even really complicated stuff now.

“With classical music, even though I’m multi-tracking I’m still thinking about getting that really good mix live in the studio then and there. So once we’ve settled on a sound, I can sit down with the score in front of me and I’m producing, and it’s all about getting a wonderful performance out of them from that point onwards. I’m always thinking with my ears trying to make sure that it’s all happening technically, but once you know all your gear so well and you’re happy that everything is set up properly, you can relax and just think about the performance and the music. That’s so much fun! And I try to make it as much like a live performance as I can. That’s what I’m aiming for as an engineer and as a producer.”

For classical music, I really love the dynamic range, the frequency range, that cleanness of digital recording

IMPERFECT RECORDINGS

All Imperfect Things: Solo Piano Music of Michael Nyman was recorded over four days in the Eugene Goossens Hall within the ABC’s Ultimo Centre headquarters in Sydney, a 400sqm performance and recording theatre that has its own control room and an SSL C200 mixing console.

Read: “My editing studio is a little room that’s next to the control room for Goossens Hall. I use my own Grace mic preamps and Grace D/A converter, straight into the Pyramix system. It’s a tidy little self-contained rig! Mostly I record in Goossens but sometimes I go further afield because you still need to go to the right venue for the music. I was at a church in Glebe in the freezing cold a little while ago recording a Gregorian chant CD, so it is mobile.

“I’ve been using little Genelec 1031A monitors for a long time, but I’ve just upgraded to these Grover Notting [Mastering Series] Code 101s. It’s a new range that Frank Hinton, down in Melbourne, has got. They’re really very nice, and he’d lent me a pair for a couple of weeks. As it happens, just I was editing and mixing Sally Whitwell’s CD.”

With regards to her approach to recording All Imperfect Things, Whitwell had a very specific sound in mind that required Read to approach the project a little differently.

Read: “This one was interesting in that Sally really likes an intimate sound — she really wants to capture the pianist’s perspective of the sound. She understands that the way you mic something actually has an influence on the expression of the CD. Invariably, all the other piano CDs I’ve recorded have been a more distant sound; I use fewer mics and the music is filling the space a bit more. This particular recording though, has a narrower dynamic range, so you can get in closer. If you’ve got really extreme louds and softs, it’s hard to get too close.

“So I had a pair of DPA 4006 omnis in a ‘spaced pair’ configuration out in the hall to pick up the piano in a more traditional way, but put an ORTF pair of Schoeps MK21 microphones, literally above Sally’s head, so they were looking down onto the hammers. You’re still getting the sense of a piano in a space, and you do hear the sound reaching out into the room, but it is also very much what Sally is hearing while she’s playing, with all that ‘oomph’, and it’s nice for people to hear that. Those low notes on the piano are fabulous! If you’re going for a more traditional distant sound, you can lose that real grunt in the piano, but we were able to capture that with this particular repertoire. So it was quite different to how I normally record a piano.”

When it comes to mastering, even with her experience in that area at Classic Sounds in the US, Read admits these days she only really masters recordings she’s undertaken herself. Though she will occasionally work on projects she’s been involved in, but have been produced by someone else, if it’s an ABC release.

“There’s a certain degree of necessity involved,” she admits. “The turnaround time tends to be quite short. But as we’ve moved from mixing things live — where more was needed out of the mastering stage in a classical recording — I’m finding, now I can multi-track, that I’m able to be much more careful with the mix and really refine it. Which means in mastering I’m not altering the sound much, or if I am, it will be to deal with some issue that wasn’t particularly solvable during recording — it’ll be something I know about before I even get to post-production. It’s better of course to solve a problem then and there, at the recording session, though some things are better dealt with at mastering.

“Lately, I’ve been doing a lot of recording involving singers and I find I’m really happy with the balance I get at the mixing stage. In many ways, during the mixing process, I’m employing mastering techniques to ensure my mix is sounding as good I can, so at mastering I find I have no desire to do any more to the sound.

“But I do definitely restrict myself to mastering classical music,” she admits with a self-deprecating laugh. “I wouldn’t dare presume to do any other genre of music. I stick to the acoustic world.”

Again, Read utilises the mastering options available in the Pyramix system but also uses a TC Electronic M6000 Mastering Processor and a Prism converter. Having until recently mastered in the main to 16-bit/44.1k, she is now accredited for Mastering in iTunes and mastering two versions of all forthcoming ABC Classical recordings.

RESPONSES